So, I had this horrible job…

Years ago I had a fairly blechy job teaching GMAT prep classes. The class met for an entire weekend (Friday night and all day Saturday and Sunday) to help prospective MBA students prepare to take the GMAT exam the following weekend.

It was a horrible job for a number of reasons (the pace, the last-minute info-cram format, the nasty windowless hotel meeting room locations, the scent of desperation in the room), but one of the biggest issues was whether or not we could actually help the students. The answer was mixed.

With a typical student we stood a decent chance of improving their Quantitative (Math, Logic, Problem-Solving) scores, but we usually couldn’t make much of a dent in their Verbal scores. I’ll explain why in a moment, but stop for a second and think about why that might be the case.

<Jeopardy theme music while you formulate a hypothesis>

Maybe it’s obvious…

… but it came down to the specifics of what we could teach them. In the quantitative section, we could teach them some quickie short cuts for math problems, remind them of the geometry formulas they hadn’t seen since their sophomore year of high school, and get them used to the wacky “data sufficiency” format that shows up on the test.

These were were a) information-based b) based on activation of prior (albeit rusty) knowledge or c) very brief skills which (in the case of the data sufficiency format) could be brought to a reasonable level of mastery in a few hours (whether they retained those skills is another matter).

In the verbal section, they needed skills like vocabulary, reading comprehension, complex analysis and reasoning. As you might imagine, these are not skills you acquire in a weekend (try decades). There are very few quickie shortcuts that you can teach someone if the foundations of their language skills aren’t there. This was amplified by the fact that right answers in the verbal section were relative right answers (“Choose the best answer”) instead of absolute (“Choose the correct answer”) — they involved judgement calls rather than calculating to find the one correct answer.

What does this have to do with buildings?

I was thinking about all of this as I read Clark Quinn’s excellent post on Designing for an uncertain world. In it, he talks about “a pedagogy that looks at slow development over time.”

This then made me think about a presentation [ppt] that Karl Fast, an information architect friend of mine, did at the IA Summit a few years back.

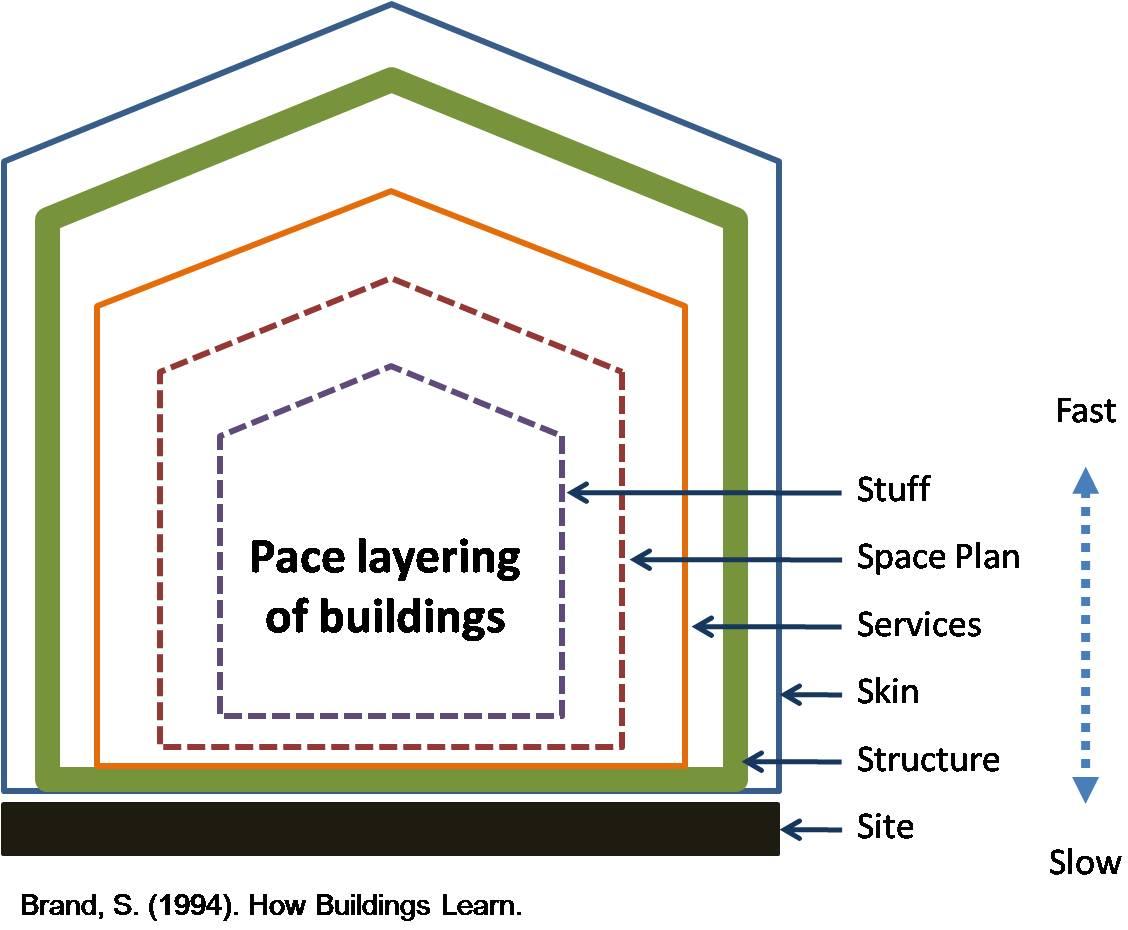

He referenced Stewart Brand’s “How Buildings Learn” (links to the whole BBC series here).

Basically, the idea is that some things change quickly (the actual contents of the room might change daily, the interior decorating might change in months to years), and some thing will change more slowly (the space usage, the interior layout, the actual structure might change in years), and some things will change only very slowly (the structure, the foundation might change in years, decades or centuries).

“The fast parts learn, propose, and absorb shocks; the slow parts remember, integrate, and constrain. The fast parts get all the attention. The slow parts have all the power.”

Steward Brand, The Long Now Foundation

He has a similar pace layering for civilization (from Brand, S. (1999). Clock of the Long Now):

- Fashion/art

- Commerce

- Infrastructure

- Governance

- Culture

- Nature

So, here’s my question — what’s the pace layering of learning?

Pace Layering for Learning

Or maybe the question is what is the pace layering of knowledge?

In the GMAT course I taught, we could, at best, rearrange some furniture (and hope that it stayed rearranged until they took the test the following week). We weren’t going to really change anything like their verbal skills – those were part of the structure and foundation.

Over the years, I’ve worked a fair number of supervisory/management skills, and you’ll bump in to circumstances where someone wants a two or three hour course on management skills (or leadership training, which is an entity unto itself).

Okay, so the notion that you can make a significant difference in how someone manages in a 2-hour course is laughable. Of course you aren’t. So what can you do?

If I think about how management skills would map to the pace layering idea (I’m not going to try to map all the levels directly):

- Stuff (easily changeable): Specific tools, techniques, concepts & principles

- Space Plan / Structure (moderately changeable over time): Skills and practices

- Foundation (slow & difficult to change): Culture, core principles, people skills and personality

Which of these is really going to make the difference in how someone is going to behave as a manager or supervisor? Remember, the slow parts have all the power.

I think there are a couple of ways this perspective could be useful:

Find a few throw pillows: What are some easy, cheap ways to make an impact? It might be a model, a tool, a job aid, a checklist — something that is easy for your learners to implement right away, that will have an immediate impact — it won’t change their world, but it might solve a small but pesky problem. Don’t try to solve big problems with a throw pillow, though. They may brighten the room, and be a cheap way to have an impact (and there’s nothing wrong with that), but they aren’t a substitute for the heavy lifting involved in real behavioral change.

Give them some sturdier pieces: Give them some more concrete material, but recognize that this is going to take more time – they will need to set it up, move it into place, get rid of the old piece, arrange it their existing stuff in it, and get used to how it changes their current patterns. You need to make sure that you don’t try to do that all at once, but recognize that there are several steps that all need to be supported, unless you want the unassembled items sitting in it’s box in the storage area indefinitely.

Recognize that you aren’t going to change their structure: If they have some renovations already in place, you might move them along a little, or you can help them start some planning for future changes. This sounds easy, but actually, it’s really hard. It’s hard because it involves letting go of the deeply held belief that we can do major renovations in short period of time. We can’t and it’s a waste of resources to pretend we can. If we approach it with the longer view in mind, we can create better ways to help people, and ensure that there is a long-term plan.

Recognize that you aren’t going to change their structure: If they have some renovations already in place, you might move them along a little, or you can help them start some planning for future changes. This sounds easy, but actually, it’s really hard. It’s hard because it involves letting go of the deeply held belief that we can do major renovations in short period of time. We can’t and it’s a waste of resources to pretend we can. If we approach it with the longer view in mind, we can create better ways to help people, and ensure that there is a long-term plan.

Respect the Foundation: The foundation is based on bedrock like culture and personal differences. If your structural changes aren’t going to sit well on the foundation, then you are better off changing your design, because it’s really unlikely that the foundation is going anywhere.

Respect the Foundation: The foundation is based on bedrock like culture and personal differences. If your structural changes aren’t going to sit well on the foundation, then you are better off changing your design, because it’s really unlikely that the foundation is going anywhere.

A couple of resources:

http://www.elearningpost.com/blog/how_buildings_learn_6_episodes_on_google_video/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dreyfus_model_of_skill_acquisition

http://www.work-learning.com/learning_factors.htm#5. Spacing repetitions and practice over time

http://wiki.bath.ac.uk/display/webservices/Shearing+layers

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shearing_layers

(I’ve seen these ideas from “How Buildings Learn” show up in Information Architecture and UX circles, but haven’t seen it applied to instructional design — has anybody seen a good application of it to learning?)

I like this post so much (for its range and for its depth) that I’m going to have to talk about it on my own blog. But there’s a sort-of-tangent bursting to get out:

For a time I taught SAT verbal test prep classes in a county near Washington DC. I tend to agree about the quantitative / qualitative difference you cite. Still, since this was a multiple-week course (I’ve repressed just how many weeks), I could and did try a couple of approaches.

I started by saying that if you did only the things we did in class, you weren’t likely to improve your score at all. There just wasn’t enough time.

But if you spent some out-of-class time applying various strategies and taking the practice tests, then, yes, you could make an improvement. In fact, if your original score was kind-of-low-to-mediocre, you could get a pretty significant boost.

Some of it was math-like: a skipped question costs you more than a wrong answer does. And when you have to guess, your odds improve if you can rule some of the choices out. (This was before the lifelines of “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?”)

In other words, I tried to help them get a few sturdy pieces, even if they were on a tight budget.

Yes — we talked about some of those test-taking tactics too, and with some time distribution, i can see how you could make more of a dent. Ours were such a last-minute, dash to the finish process that I was never really sure if we accomplished anything.

But that story has been incredibly useful to me over the years – I’ve told it to countless clients to help them understand the importance of distributed practice, more realistic objectives, and longer term planning.

And I was explaining the pace layering concept to a client just today, in fact

Julie and Dave,

I will probably have more substantive comments on this in-depth article later, but isn’t it funny how many of us have a background in teaching standardized test prep?

Did you teach for the red company or the purple company, or someone else? Red here… 10 years! Whew.

Neither — I was the operated-out-of-some-guy’s-closet company

It was somebody who had built a business doing LSAT classes, and was trying to expand into other tests. Eventually, he stopped doing it, and went back to just doing the LSATs. When he stopped, he told me not to bother shipping any of the supplies back, so i got a dozen or so GMAT test prep books, and a really nice electric pencil sharpener. For years afterwards, my ears would prick up whenever i heard reference to the GMAT – “Hey! Let me give you a book…”

I love this post. Expect to see faint echoes appear on my blog over the next few months…

I did GMAT preparation classes over 12 weeks with Italian students who were smart enough (or, more likely, had smart enough parents) to realise how terrible their own university education was. Them being Italian (and me being rubbish at maths), I did the ‘verbal’ bit and essay coaching. Here’s a tale of Three Summers.

Summer One: I taught them about ‘the text’ and saw rapid early improvements, which then flatlined. Students liked the course – I have no idea if they went on to succeed in the GMAT.

Summer Two: I became a GMAT guru and taught a course focused on ‘exam technique’. This was my entirely cynical version of Dave’s ‘sturdy piece’ and based on my realisation that I had little chance of teaching them anything about writing in a few short weeks beyond a bit about essay structure (ie ‘the text’). Students adored the course – I have no idea if they went on to succeed in the GMAT.

Summer Three: I did a couple of lessons about ‘the text’ at the beginning of the course. And a couple of lessons about technique at the end. For the rest of the course, I got them to watch/read controversial films, documentaries, TV shows and articles. At some point, I’d realised that these Italians weren’t so much lacking in verbal skills as they were suffering from a deficit of having anything to talk/write about. And I ranted about this: you can work all you want on your grammar and your practice essays, but if you don’t know anything about the world you’ll never get in! Grammar is just the icing on the cake! But first you need a cake etc

It was all very Dead Poets.

The students were almost perfectly ambivalent about the course (some even complained about me being ‘lazy’, which was ironic considering the massive amount of effort I put into doing this one in comparison with the previous two). About six months after the course, I got two letters of thanks full of the most gushing praise, albeit with language constructed as if designed to undermine the whole effort.

At work, we almost never have the time or resources to change learners’ ‘structure’. Which is ironic, given the zealous tone of a good deal of the ‘change’ programmes I’ve been involved with.

But the flipside of this is that, if you do have time to carry out a bit of structural renovation, it’s worth doing that at the expense of all else.

PS Good to see that everybody’s done some of this standardised test stuff. I did countless hours of planning and delivery of the stuff. It’s (often) wasteful for students but I learned a fantastic amount – where else do you find such detailed and timely feedback than in ‘teaching to the test’?

Odd that such superficial teaching has had the most ‘structural’ effect on me as a practitioner. I wonder if there’s a link?

It’s odd for me too, how much that relatively minor experience continues to come up, and impact the way I think about designing instruction.

I’ve told that story countless times to clients, to help get them to a realistic place in terms of what they can accomplish in a single course. I wish I could say that I’ve also equally used it to help them think about long-term structural learning experiences, but not so much.

I’m pretty infatuated with the pace layering metaphor though — I pretty much want to figure out the pace layering of *everything* (“hmm, what’s the pace layering of my refrigerator?”).

I do agree that people are like buildings because we all learn at different rates and pace. Each area of a building is design at different times and people learn at different rates slow or fast depending on the information. A manager in a building is like a teacher in a classroom. A teacher known his/her students learning skills, speed, and the pace they can learn. A teacher must help a student understand the topic like creating a foundation of core principles, people skills, and personality. The pillow example is a great way to express the importance of providing students the skills to help them involve into a great individual in today’s environment like in a structure of a building.

Thanks for the comment, Katie. It is a critical skill for teachers, isn’t it? I think one of the hardest things about f2f teaching is dealing with the varying skill levels in the room — some people are building foundations, while others are decorating, and learning how to balance all that was one of the hardest skills for me to master when I started teaching.