Just had this quick interchange with Patti Shank on twitter:

This is a totally fair comment on Patti’s part — you can’t force someone to be motivated (and undoubtedly some of our disagreement stems from semantics – not that THAT ever happens on twitter). A lot of the conversation around gamification (for a heated throw down on the topic read the comments here) is about the dubious and likely counterproductive effects of extrinsic rewards as motivators. According to Alfie Kohn in his book Punished by Rewards, a big part of the problem with extrinsic motivators is that it’s about controlling the learner, not helping or supporting them.

So that I totally agree with – you can’t control your learner, or control their motivation.

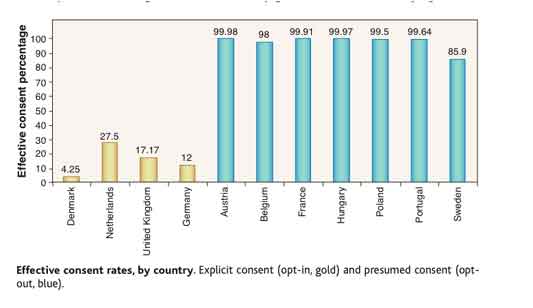

But design decisions do have an impact on human behavior. For example, this chart show the rate of people who agree to be organ donors in different European countries:

In the blue countries, choosing to be a organ donor is selected by default, and the person has to de-select it if they do not want to be a donor. In the yellow countries, the default is that the person will not be an organ donor, and the person has to actively choose to select organ donor status.

In the blue countries, choosing to be a organ donor is selected by default, and the person has to de-select it if they do not want to be a donor. In the yellow countries, the default is that the person will not be an organ donor, and the person has to actively choose to select organ donor status.

Now it could be that some people aren’t paying attention, but at least some of that difference is presumably due to people who do notice, but just roll with the default (you can read more about it here – scroll down to the Dan Ariely section).

So the way something is designed can make a difference in behavior. Of course, that’s not a training example, so let’s take a closer look at how training might come in to play.

Is it a training problem?

Robert Mager used this question as a litmus test:

“If you held a gun to the person’s head, would they be able to do the task?”

He further discusses this in his book on Analyzing Performance Problems but later uses the less graphic “could they do the task if their life depended on it?” question (Thiagi advocates for the version “Could they do it if you offered them a million dollars?” if you prefer a non-violent take).

So basically, if someone could do the behavior under extreme pressure, then they clearly know how to do it, and it’s not a knowledge or skills problem, and therefore outside of the domain of training (could be up the person’s specific motivation, could be a workplace management issue, etc.).

Here’s where I disagree

I think the way you design learning experiences can have an impact on the likelihood of people engaging in the desired behavior, and that it is part of an instructional designer’s responsibility. I don’t think you can control people, or force the issue, but I do think the experience they have when they are learning about something can make a difference in the decisions they make later.

There are a couple of models that influence my thinking on this, but the two I use most often are the Technology Acceptance Model, and Everett Rogers Diffusion of Innovations.

The Technology Acceptance Model

The technology acceptance model is an information systems model that looks at what variables affect whether or not someone adopts a new technology. It’s been fairly well research (and isn’t without its critics), but I find it to be a useful frame. At the heart of the model are two variables:

It’s not a complicated idea – if you want someone to use something, they need to believe that it’s actually useful, and that it won’t be a major pain in the ass to use.

TAM specifically addresses technology adoption, but those variables make sense for a lot of things. You want someone to use a new method of coaching employees? Or maybe a new safety procedure? If your audience believes that it’s pointless (ie not useful), or it’s going to be a major pain (ie not easy to use), then they will probably figure out ways around it. Then it either fails to get adopted or you get into all sorts of issues around punishments, incentives, etc.

I keep TAM in mind when I design anything that requires adopting a new technology or system or practice (which is almost everything I do). Some of the questions I ask are:

- Is the new behavior genuinely useful? Sometimes it’s not useful for the learner – it’s useful to the organization, or it’s a compliance necessity. In those cases, it can be a good idea to acknowledge it and make sure the learner understands why the change is being made – that it isn’t just the organization messing with their workflow, but that it’s a necessary change for other reasons.

- If it is useful, how will the learner know that? You can use case studies, examples, people talking about how it’s helped them, or give the learner the experience of it being useful through simulations. Show, Don’t Tell becomes particular important here. You can assert usefulness until you are blue in the face, and you won’t get nearly as much buy-in as being able to try it, or hearing positive endorsements from trusted peers.

- Is the new behavior easy-to-use? If it’s not, why not? Is it too complex? Is it because people are too used their current system? People will learn to use even the most hideous system by mentally automating tasks (see these descriptions of the QWERTY keyboard and the Bloomberg Terminal), but then when you ask them to change, it’s really difficult because they can no longer use those mental shortcuts and the new system feels uncomfortably effortful until they’ve had enough practice.

- If it’s not easy to use, is there anything that can be done to help that? Can the learners practice enough to make it easier? Can you make job aids or other performance supports? Can you roll it out in parts so they don’t have to tackle it all at once? Can you improve the process or interface to address ease-of-use issues?

Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations

- Relative Advantage – the degree to which an innovation is perceived as being better than the idea it supersedes

- Compatibility – the degree to which an innovation is perceived to be consistent with the existing values, past experiences and needs of potential adopters

- Complexity – the degree to which an innovation is perceived as difficult to use

- Trialability – the opportunity to experiment with the innovation on a limited basis

- Observability – the degree to which the results of an innovation are visible to others

There is obviously some crossover with TAM, but If I’m designing a learning experience for a new system, I use this as a mental checklist:

- Are the learners going to believe the new system is better?

- Are there compatibility issues that need to be addressed?

- Can we do anything reduce complexity?

- Do the learners have a chance to see it being used?

- Do the learners have a chance to try it out themselves?

- and, How can they have the opportunity to have some success with the new system?

Now, if somebody really, really doesn’t want to do something, designing instruction around these elements probably isn’t going to change their mind (Patti’s not wrong about that). And if a new system, process or idea is really sucky, or a pain in the ass to implement, then it’s going to fail no matter how many opportunities you give the learner to try it out.

But here’s the thing – I can design a training intervention that can teach a learner how to use a new system/concept/idea, which could meet the Mager requirement (they could do it if their life depended on it), but I will design a very different (and I think better) learning experience if I consider these motivation factors as well.

I don’t want to take ownership of the entire problem of motivating learners (waaaaaay too many variables outside of my scope or control), but I do believe I share in the responsibility of creating an environment where they can succeed.

And bottom line, I believe my responsibility as a learning designer is to do my best to motivate learners by creating a learning experience where my learners can kick ass, because in the words of the always-fabulous Kathy Sierra kicking ass is more fun (and better learning).

—————————————

References

Davis, F. D. (1989), “Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology”, MIS Quarterly 13(3): 319–340

Johnson, Eric J. and Goldstein, Daniel G., Do Defaults Save Lives? (Nov 21, 2003). Science, Vol. 302, pp. 1338-1339, 2003. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1324774

Mager, Robert and Pipe, Peter, Analyzing Performance Problems: Or, You Really Oughta Wanna–How to Figure out Why People Aren’t Doing What They Should Be, and What to do About It

Rogers, Everett Diffusion of Innovations

Been thinking about this one a lot recently because of recent work experiences – from the perspective of ‘raising awareness’ as a Learning Objective.

(It’s related to that recent ‘I am a learner’ piece too. I think there’s a thing where we know, deep inside, that it’s not about teaching or training or ‘input’ but learning and personal development. But, it’s still our job, dagnabbit. And too much of the social learning conversation has the ring of, “Hey, our job is done! Let’s make friends with learners on Facebook!”)

We all know it’s a bad thing to have something as useless as ‘raising awareness’ as an objective, but, let’s face it, it’s still at the heart of half the training/learning plans I see. I’m being generous here, I reckon.

I think there’s something related to the Overton Window:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Overton_window

(Jay Rosen calls this, or something similar at any rate, the Zone of Legitimate Controversy in a more sociological vein.)

Having somebody spend half a day in a workshop, or a few hours eLearning (or even reading a book) seems like a fairly good use of time if you can open an Overon Window of confidence, enthusiasm or even possibility.

In a way, why not have ‘motivation’ as an objective, if you have the chops to pull it off – and have ‘learning’ as something scheduled for outside the classroom/course?

I’m being contrary, a little. But a lot of the ‘it’s not teaching it’s learning/our job isn’t to motivate’ seems like a disavowal of responsibility to me. Like I said, a little.

Thanks Simon – I like the Overton Window notion — that kind of awareness is necessary (if not sufficient).

I’ve been trying to set more realistic expectations with clients lately — I keep hearing things like “We want the learners to be fully proficient at using all the features and benefits of this product in the sales cycle, but we need to keep the e-learning under 30 minutes.” #expectationsfail.

Another thing I wonder about is the complete lack of crossover in the field between marketing and training — is anybody doing that? We say we are about behavior change, but there doesn’t seem to be anyone learning from the marketing folks (who, after all, are the diabolical geniuses of behavior change, even if it’s mostly about ‘buying-stuff’ behaviors). Similarly, we (as a field) still pretty much suck at metrics, but could learn from sales and marketing, who metric the hell out of everything.

A thing that marketers have (UX is a great example of this) is a healthy disrespect for established science or theory.

What I mean by this is, you often have to start from a position of little or no accepted information — no canon, no SME, just a semi-logical supposition. And then you iterate on top of that. Sure, if you’re smart, you’ll have all that science and canonical stuff in the background. But, as marketer, you’re often trying to stimulate activity/response rather than transfer knowledge. The worst UXes I’ve worked with are the ones who are always referring back to stats quoted in Jakob Nielsen newsletters without any sense of the current context. The worst trainers are similar. “Hmm, that’s funny, the manual says they should have learned something by now…”

Anyway, ‘motivation’ is detectable and you can metric the hell out of it. Sometimes it’s the only metric available.

I should say, gently, in my line of ‘training’ work, motivation is often ‘sufficient’. I tend to do my work in ‘distressed’ or entirely novel situations where there are no neat performance objectives available. You take what you get – you ASTD types live in a weird little professional bubble (see Louis Menand’s Interdisciplinarity and Anxiety – http://humanities.princeton.edu/fds/MenandInterdisciplinarity.pdf). You’d be horrified at what goes on in my world

____

Quick suggestions: TAM is cool. TALC, for organisation or Development types, is probably usefuller? Crossing the Chasm by Geoffrey Moore is a must-read.

BTW, It’s funny — I thought that training/marketing thing was kind of my thing (I do more marketing work than learning stuff these days, and more ‘Change’ than either of those).

I guess it seems soooo obvious to me that marketing permeates everything, I don’t bother to highlight it enough. One to ponder, though it’s partly because the term ‘marketing’ is one of those irritating words that everybody thinks they understand but almost nobody does. Sadly, this includes marketers who fail to see the difference between them and sales/advertising. Sadface.

Agree agree agree!

If anything has shifted for me over the last decade, it is my belief that our role as UX, game, or LX designers is to motivate. We already know that when motivation is strong, learners/users are capable of suffering through a world of crappy learning materials, and we also know the opposite is true… Beautifully-crafted, expertly-tuned, “neuron-friendly” instruction that leaves the learner with knowledge they’ll never care to use. Even if their OWN life IS at stake, in some cases (see “change or die” Fast company article or book of the same name).

I feel that I am always responsible for at least two different forms of motivation related to learning: motivation for the topic (including every tiny subtopic) AND motivation to actually *use* what was learned. Even those who come IN motivated to learn topic X still have brains looking for more interesting things to attend to, and if the why/why cares of a subtopic is not set-up in a compelling way, then why SHOULD they pay attention? This first kind of motivation is the one that keeps them alert and engaged start to finish, on each new page of a book, on each new slide in a presentation, and on each new concept on the white board.

The second motivation — the one that drives behavior — is often taken care of if the first kind is well done, but of course in Corp training there are million other reasons why it might not be happening. But they we have an ethical question… If we *know* a training solution is pointless because the system is so poorly designed for use, then why are we even trying to motivate people to do it the awful way? But often, the answer is somewhere in between… There really IS a compelling benefit for the learner/user in doing it this way, but we just haven’t made the motivating, compelling case. That IS on us, as instructors of anything.

Love this post. Thank-you.

(and of course if we are down to extrinsic motivators, then we are pretty much already screwed anyway, unless it is for rote, tedious tasks… But my points relate to topics where there could be intrinsic motivation if the learner is allowed and encouraged to develop higher competence and resolution in an interesting “intrinsically rewarding” way…)

Kathy – I think the distinction between motivation to pay attention, and motivation to actual do things is really useful. This post is about the latter, but I’ve been thinking a lot about the former lately (just wrote a chapter about it, actually – let me know if you’d like to see it).

There is definitely an ethical issue — I I shouldn’t be trying to convince you something is ease-to-use (or useful) if it isn’t actually. Also, as mrsmoti and Patti observed below — it’s not like people can’t figure out they are a being handed a line. All you accomplish is blowing your credibility and making your learner’s feel like they’ve been bait-and-switched.

I also agree that it’s also demoralizing to have to use training to help people around crappy interfaces, too. Any number of times, I’ve thought “Seriously? They have to do what? Can’t we just fix the interface, and then you won’t need training?”

Wonderful stuff.

And raises issues connected to instruction and new technology being used in a glib way, as the fashion of the hour, or a political way, to enhance the reputation of the person/people introducing the change.

In UKs best known industrial democracy, a retail biz, we introduce all training by discussing what learners might gain and lose from their learning , and investigate where and how learning will be useful.

I know big abstract nouns can be open to misinterpretation, but it’s about integrity and empathy between deliverer and recipients, isn’t it?

Thanks! I agree — the integrity & empathy pieces are crucial whenever you move from purely informative to persuasive.

Btw – I’ve been thinking more about your vividness comment from that previous blog post…mulling it along with some other ideas for a future post possibly…

Terrific and looking forward in anticipation…

This may be useful http://psp.sagepub.com/content/37/5/626.abstract .

Am sure you aware much psych research on this relates to health education and behaviour change.

Thoughtfulness and clarity in your posts outstanding in my view- and much appreciated.

We agree. So I guess our disagreement was mostly semantics after all. My main issue was that you can’t manipulate people. They smell that a million miles off and will do almost anything to subvert it. The other issue is that we shouldn’t be hiring people with the intention to motivate them into doing what we want them to do. For example, if we want people to be nice to customers, we should hire people who have that attribute. It’s almost impossible to train grumpy people to be nice to people. You CAN train people to smile and say the right words but grumpy people can DO those things and customers still know they’re not really being nice. (C’mon, you’ve had those kind of people wait on you.)

I also think that there are plenty of times when we’re tasked with trying to motivate learners to do X when we SHOULD be trying to motivate the stakeholders to change the way things work because the way things work DOESN’T WORK. Someone has to stick up for learners and if we don’t, no one will.

Yes — I suspected were weren’t really that far apart.

Regarding sticking up for the learners – absolutely, and that goes to my issue with training being as silo-ed as it so frequently is — I really think that we need to get better about that as a profession (being more involved in the bigger conversation – not just the “training” piece).

I’m so glad I subscribe to your blog so I didn’t miss this post. Very nicely written. Your post motivates me: the organization alone kept me motivated to read on. And that’s our job as trainers: organize info for learners.

I’m happy to see your points about designing for one audience or designing another way for a different audience. I wonder what you think about elearning class sizes. I wrote a bit about it (shameless plug: http://elearningweekly.wordpress.com/2010/10/13/whats-your-elearning-class-size/ ) and I’d like to read your thoughts about it.

(Or we can get coffee in Minneapolis and discuss!)

Best,

Eric (Editor, eLearning Weekly)

Thanks Eric.

Coffee = sure! I’d be interested in understanding more about your post about class size — might be good to chat about it (although I did comment on it when you posted it, but mostly with questions).

Glad you enjoyed the post.

Very interesting discussion. I’m fascinated with the effects that UIs and design in general have on motivation and engagement.

But perhaps the biggest lesson here is that Twitter isn’t the place for discussing anything of complexity:)

Thanks Yoni – there’s a lot of interesting stuff coming out about persuasive design and behavioral nudges. Have you seen BJ Fogg’s stuff? http://www.bjfogg.com/

I also like Stephen Anderson’s stuff for practical web applications http://amzn.to/q4mOiL and http://getmentalnotes.com

Agree that complexity is tough on Twitter (although I’ve seen it done, with enough effort), but it’s a lovely jumping off point

Nice Article. Something that have not seen in instructional design is the use of loss aversion. If you are trying to nudge someone in a direction (open them to something new) present the situation in a way that if the course of action is not changed they will lose something. People will be open to change their thinking if they feel they will lose something. You can use this technique gently to get people to think/feel differently.

Work on germane cognitive load speaks to this as well. Germane load — how hard it is to learn a task — is tied to motivation and interest. As designers we can have a good deal of influence over that. We can’t make someone get out of bed in the morning, but we can make a program more relevant, worthwhile, interesting, and ‘motivating’. As you said, ” I share in the responsibility of creating an environment where they can succeed.” Well put.

I really enjoyed this post & plan to pick up those books and read on – or maybe on the Kindle, then accessible anywhere

I agree that we need to address motivation and not just become “elearning” creation robots. Really thinking about what the users/learners need I think is the key – they need to know and BELIEVE the WIIFM – and the WIIFM we present needs to be real.

Thanks again for a great post!

Meg

I believe that motivation is an integral part of creating effective instructional design. Of course, you can’t force anyone to do something, but I don’t see how you can leave this factor OUT when developing design. Business training is tied to business goals. You want someone to be able to do something or change behavior.

This is real world stuff. We aren’t creating courses just to be creating courses. Human beings require motivation in order to change behavior or adopt new skills.

We need to support this inner motivation by letting them know how it will benefit them and how the change relates to their present jobs. We need to create training that is interesting and intelligently designed to enable them to understand and adopt the changes. We need to do a better job with encouraging information transfer to the job.

We have constraints as instructional designers, but we have a responsibility to do the best we can within these constraints. We are not “off the hook” because we can’t control everything.

Learning. Motivation. Performance. These are all things we have to believe that we have some influence on if we are to be successful as ID’s. Not control. Influence by design.

This might not mean that we can *directly* increase motivation. But we CAN improve the probability that the learner will create their own motivation if we do what’s necessary to get to know the types of learners we’re dealing with and the tasks we have to support. We can also consider the psychological impact of elements that can seriously degrade motivation (anti-motivators). So if there’s a line; on one side of the line we see the varying influence probabilities (stuff we do) and on the other side are the factors completely in the learner’s control… What are the upstream factors that can enhance or degrade uptake, performance, and motivation? Stuff like authenticity, respect (of time / intelligence) — variables that, when absent, can degrade motivation.

A good friend of mine recently started some work extending Keller’s ARCS model. A presentation of these enhancements and some of his observations are here (http://www.robisonperformance.com/#!__papers). You can see a video of Don presenting these observations here (http://www.uscghpt.org/_lib/2011sessions/Why%20They%20Do%20What%20They%20Do_Sys%20View%20of%20Motivation.wmv) and his slides here (http://www.uscghpt.org/_lib/2011sessions/DRobinson_15Sep_1510-1600.pdf).

I bought your book, by the way. I think the tone and pace is great! I’m enjoying it so far.